Critique is just a cutting tool, not the price of admission. A device for making little breathing holes in the suffocating fabric of reality.

—Marina Vishmidt

This exhibition in two parts—programmed by Broadside and Ivory Tars—engages with Infrastructural Critique, a term coined by the late theorist Marina Vishmidt (1976–2024).

Infrastructural Critique seeks to problematise the limited scope of earlier forms of Institutional Critique, in order to create an immanent space in which the material conditions of contemporary life can be better apprehended and gestured beyond. Whilst not an attempt at a direct explication of Vishmidt’s far-ranging thoughts on the subject—there is no formal style or procedural approach that can be applied to her theories, and they are inimical to any overarching scheme of visual representation—this project acts as a provocation. As a way of articulating a series of operative contradictions around which these theories revolve.

Paul Sullivan’s Noodle Bar is a long-running, intermittently developed project that began in 2008, operating in the ambiguous space between art, architecture and social intervention. Underpinned by an interest in immigration, urban planning, and the exceptional status of the artwork, the project took the form of a functioning noodle bar operating from a converted shipping container appended to Static — the Liverpool gallery and studio complex Sullivan has directed since 1995. The project emerged from a number of sources including an interest in the displacement that takes place in Manets the Bar at the Folies Bergere, memories of the 1985 film Tampopo, and Sullivan’s own discomfort with following a path as a commercial architect being more interested in ways that he might use his training in a guerilla fashion. The project was deliberately layered with contradiction. Staffed by Koreans recruited in Seoul through advertisements featuring imagery of The Beatles — leveraging the city’s most famous export to attract the workers—the bar was a functional enterprise built to push at the limits of urban regulation. Sullivan made use of existing systems; by officially designating the venture as an artwork for the Liverpool Biennial’s fringe program, he shifted its legal framework, subjecting it to a different set of rules than those governing a restaurant or building. This move had a profound material consequence: when visas for the Korean workers were initially denied, the simple act of reclassifying them as ‘artists’ participating in an international exhibition suddenly made them eligible, laying bare the arbitrary and performative nature of bureaucratic systems. However, the project’s critical success soon met with human complication. Relations between Sullivan and the workers — Kim Ji-Sun and Park Hy-Lan — quickly soured. The realities of living and working in an unfamiliar city, under the strained premise of an art project, proved difficult. In the end, they only stayed for a matter of days before choosing to leave Liverpool altogether, relocating to New Malden, the established heart of the Korean community in the UK. Presented here as a skeletal sketch of the shipping container foreshortened to account for the different space with the traces of the original work appended to the structure in a manner akin to crash site investigation. This reconstruction is to be used as a way to revisit the fractious relationship with the workers and Paul, cognisant that to date he has been the one to tell the story, will reach out to to gain some insight into how it felt to be involved from the other side.

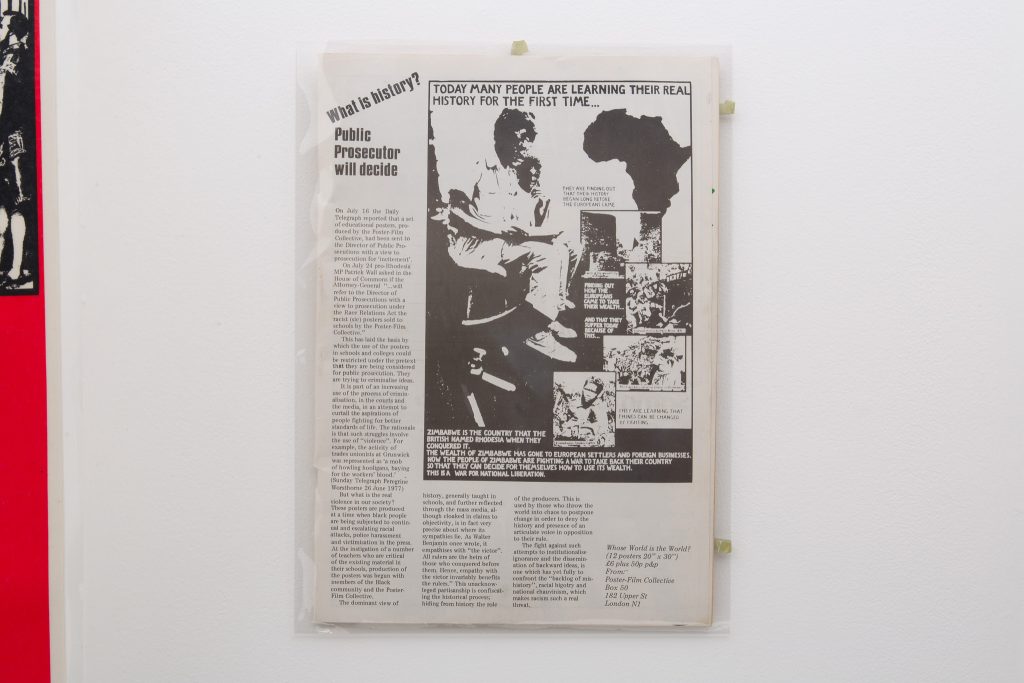

Poster Film Collective were active from 1971 through to the end of the 80s and initially came about through a frustration at the conservatism of the Slade where they had met and shared an interest in how their skills could be put to a more direct political use. The work here Whose World is the World? consists of a set of 12 posters telling the history of colonialism produced by the collective from their workshop in Tolmers Square, Camden and commissioned by the Greater London Council made with schoolteachers to use as a visual aid in order to address what was rapidly becoming a multicultural society. Alongside this is material related to how the Blue Monday Club — a far-right pressure group within the Conservative Party — sought to frustrate the posters distribution via legal means.

Core members of the collective were Bernadette Brittain, Andrew Darley, David Fox, Judith Fox, Christine Halsall, Jonathan Miles, Nancy Schiesari, Steven Sprung, Silvia Stevens, Martin Walker and Annie Grove-White.

Channels was a short-lived feminist art collective consisting of Rachel Baker, Lizzie Homersham, Dimitra Kotouza and Marina Vishmidt. In this exhibition we are presenting the 2017 work This is a Window. As Marina’s long-term partner Danny Hayward wrote in the special issue of Variant published in May of this year:

‘In many ways, this short film contains the entire problem of infrastructural critique as Marina would go on to develop it. In the opening sequences, we see a picture of four women eating while a fifth bathes naked in the sink in a women’s squat in Rosetta Street, South London in 1974, along with images of Marina’s own kitchen in Hackney, East London, shot through a wall-hatch from the living room next door. ‘Generally’, Marina suggests gently on the voiceover, ‘washing is not conversational’ and ‘does not usually share space with dinner parties’. Yet the ‘mediations’ or more simply the walls in this image have collapsed, and in place of two distinct reproductive and social ‘institutions’ we see the sinuous outlines of one, a domestic moebius strip: ‘a home dwells folded into itself as an institution and then transits as if whole and unharmed into another institution, so a ground that also feels like a container’.’